34

What is social presence?

Social presence is the ability of participants to identify with the community (e.g., course of study), communicate purposefully in a trusting environment, and develop interpersonal relationships by way of projecting their individual personalities.

(Garrison, 2009)

The above quotation is Garrison’s most recent definition of the concept of social presence in online courses. Just like teaching presence, social presence (or a lack thereof) is an experience rather than a specific situation. Social presence arises in online courses when everyone involved in the course has a chance to be known to some degree as a unique person with their own personality, and further is able to interact with other such people in the interests of learning together.

Why social presence matters

While online courses may only rarely produce deep and lasting relationships between participants, such deep connections are not necessary for a successful course. Instead, what is crucial is for learners to feel that they are known and recognized to at least some degree and that they know and recognize others in the course community. This sense of being known, and of interacting with other known people, plays a vital role in learning almost anything because learning is a fundamentally vulnerable experience. After all, learning involves an admission that one does not already know what one is intending to learn.

Have you ever been in a room where you were the only person who didn’t know something? Think back to what that was like for a moment.

Now compare that type of experience to a situation in which you were among many fellow learners with the same questions as you and seeking to learn the same things as you. In which situation is it easier to learn?

If you picked the second situation, you already have an intuitive sense of the importance of social presence for learning. As Garrison’s definition above and your own experience both show, social presence helps learners to feel secure instead of vulnerable, allowing them to more easily take the intellectual risks necessary to learn new facts and skills, and to work with new ideas and processes for the first time. While social presence often builds naturally in in-person courses, fostering social presence online requires more deliberate work both for you and the learners in your course. However, when planned for and facilitated effectively, social presence can and does arise in online courses—sometimes even more than in person!

Strategies for fostering social presence

Signalling your presence

Encouraging social presence in your online courses begins at the level of design. Making sure that your learners will have opportunities to engage with one another in a variety of ways is the most important step you can take to creating social presence in your course. Community building activities from Module 2 can help in building this social presence.

Whether or not you designed your course, there are a few things you’ll want to keep in mind about learner–learner interaction and social presence while you are teaching during a course offering.

Discussion forums are like dinner parties, and the instructor is the host. Personally welcoming each student into this new and unfamiliar place and making them feel like they belong in that environment is a necessity to help integrate them socially and academically into the course.

(Hayek, 2012)

As with every aspect of online design and teaching, signalling your presence in the social spaces of your course is crucial for fostering deeper learner–learner interaction and thus humanizing the online course experience for everyone. While social spaces are typically not where most course content is shared in online courses, you still play a crucial role in helping learners to feel welcome and encouraged to participate in every aspect of your online course. Thinking of yourself as a host, as in the quotation above, can be helpful for framing your role in encouraging learner–learner interaction during term.

Your presence and investment in the social life of your course can be signalled in a variety of ways, including the following:

- facilitating discussions actively by sharing prompts and questions as the term progresses;

- actively posting in discussions and other forums throughout the term (see the next section for more on how much and how often to post);

- summarizing key discussions after the fact, whether inside the discussion itself or through an announcement or other message;

- participating in social spaces in your online course, such as general chat forums or course-related social media threads;

- checking in on learner interactions, especially group work, to make sure things are going smoothly and to help with any problems that arise; and

- offering virtual office hours, if not every week, then in the weeks preceding large assignment deadlines or midterms/finals. By opening a video conference room for a set amount of time (e.g., one hour), you allow a space for learners to chat with you synchronously and perhaps more informally.

Examples of fostering social presence

Quality Essential

Example 1: Socratic prompts

Consider using some of these prompts to help forward conversation in your discussion forums.

Online Discussions Socratic Questions (PDF)

(Paul, 2006)

Quality Essential

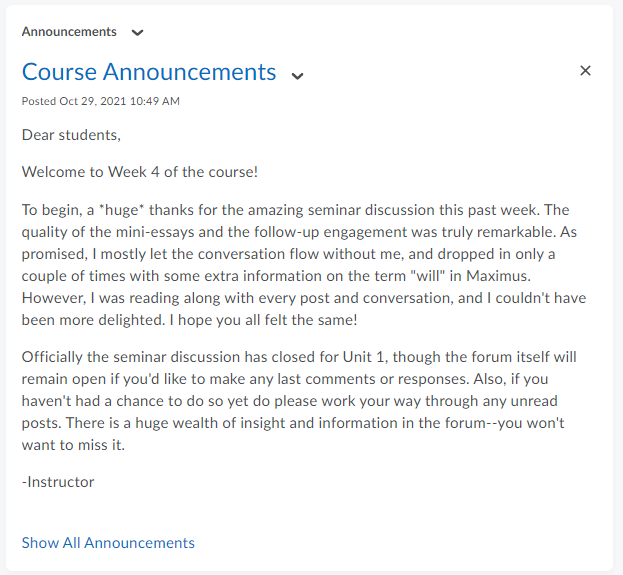

Example 2: Course announcement

Here is a real world excerpt from a course announcement signalling the instructor’s interest in a previous week’s forum discussion.

Credit: Daniel Opperwall, Trinity College, University of Toronto | Image description [PDF]

Balancing your involvement

How much should you post to discussions and participate in other learner–learner interaction spaces in your course? As with so many things, the answer is seldom simple, and effective presence in social spaces involves striking the right balance given your learner population, the nature of your course, and your own teaching style.

Instructors should jump in quickly when they see [a] discussion in the thread is wrong or getting well off track; otherwise hold back for the first week and let the learners have at it. Coming in too early with comments tends to shut down the discussion.

(Mazzolini & Maddison, 2007)

On the one hand, research shows that more frequent posting by instructors in course discussions is correlated to less frequent posting on the part of learners (Mazzolini & Maddison, 2007), which may in part be caused by learners feeling they have less to add to certain conversations after the instructor’s opinions have been shared.

On the other hand, sheer frequency of posting may not be the only thing to consider regarding the overall impact of various interactions in your course (Mazzolini & Maddison, 2007). For instance,

- sharing accurate information and clearing up learners’ confusion as an instructor have obvious positive impacts on learner understanding even if doing so results in less follow-up discussion, and

- instructors who post frequently are rated by learners as more enthusiastic and as displaying greater subject matter expertise (Mazzolini & Maddison, 2007).

Such perceptions on the part of learners can be useful in creating instructor presence in your course. In short, posting too much can stifle conversation in online classes, while posting too little may make you seem distant and allow learner errors to go uncorrected.

As you navigate the tightrope act of how much to involve yourself in discussions and similar spaces, consider the purpose of a particular interaction or assignment.

- For discussions that are meant to encourage learners to get to know one another, as well as those that are more seminar or opinion-based, you may wish to have a lighter touch with respect to your immediate presence.

- For discussions that focus more on learning content, especially fact-based materials, it may be worth weighing in more often to keep learners on the right track even if they post less frequently afterward.

Responding to conflict and poor netiquette

Conflict and disagreement are natural in academic discussions and are not necessarily a problem in online courses when navigated carefully. However, when conflict heats up to the point that etiquette breaks down, or begins to monopolize a conversation, it can start to be a problem. Asynchronous discussions in particular can present challenges as learners may read one another’s words less generously and with less context than they would have when speaking in-person. When signals like body language and tone of voice are not available, conflicts can escalate quickly.

One of the most important steps you can take to mitigate conflict in your online class to is to make sure your expectations for how learners will treat one another in their discussions are extremely clear. Spell out for your learners what good online etiquette (sometimes called “netiquette” or “ground rules”) entails and how you expect them to speak to one another, especially when disagreeing. Consider making netiquette a component of learners’ participation or discussion marks to further encourage good discourse.

If problems still arise during the course consider

- contacting the individual learners involved and reminding them of your expectations and requirements;

- reminding the class as a whole, in general terms, of your netiquette policies (never call out specific learners for violations of these policies in public, however); or

- intervening in a discussion where possible to mediate potential conflict, especially if you perceive a misunderstanding or failure of communication.

In addition, strive to humanize the environment around your course discussions by helping learners get to know each other. If possible, encourage or require learners to post photos of themselves and/or aspects of their lives like pets, family, homes, and communities as much as they are comfortable. Be sure to spend some time breaking the ice at the beginning of your course. And when conflicts do arise, help draw learners back to the mutual recognition of one another as real people with feelings and values of their own. The more human an environment you can create, the less problem conflict you are likely to encounter in online discussions.

An EDII perspective: Accountable spaces

It is normal to have difficult or challenging academic discussions in postsecondary education; indeed, this is part of the path to education. However, learners are often in a vulnerable position especially when discussing sensitive or controversial topics. When we create an accountable space, we allow space to validate students and their experiences, and are able to engage differently or challenge them to think differently. “Ground rules” (like a social contract) for discussions outline expected behaviours of all learners (and the instructor) and offer avenues for resolution and consequences for poor behaviour. These can either be presented to learners (i.e., through the syllabus) or cocreated. Creating such an accountable learning space creates an inclusive space.

This is not to say we cannot have difficult conversations, but rather an examination and explicit conversation of how we will have difficult conversations and how we will respect different ways of knowing.

What may be a challenging extension to this idea is that we do not strive to guarantee safe space and a safe space is not for everyone.

What do we mean by that?

We mean that it is important that our entrenched ideas, perceptions, and knowledge (especially harmful, negative, or incorrect dominant views) are unsettled and that there is positive learning and growth; at the same time, we need to take action to ensure marginalized learners are protected. Actively stepping in and addressing problematic behaviours and checking in with learners that you recognize as having been explicitly or implicitly targeted are important ways to model this behaviour.

This approach is often framed in antioppressive or antiracist pedagogy and practice. The principles and actions of these pedagogies serve to create a better learner space for everyone. We have only lightly touched on these ideas in this course; we encourage you to continue learning about these approaches for more inclusive, brave, and accountable spaces.

Presented are three resources to support your learning journey.

Responding to lack of engagement

Shallow responses and lack of engagement are a common problem in asynchronous online course discussions. Encouraging vigorous participation from all learners is a great way to improve everyone’s online course experience.

Once again, the most important step to take to encourage participation is to be extremely clear about expectations for participation online. Basics, like the number of posts required and how often learners need to engage are of course essential. But consider digging deeper and providing learners with further guidance about what makes an effective and engaging discussion (or other asynchronous) post by providing

- clear rubrics, which can be helpful for letting learners know what you expect;

- detailed descriptions of what makes for good posting and engagement; and

- examples (if possible) of good posts that learners can emulate.

If certain learners nonetheless seem disengaged, are posting very little, and/or are only posting short responses like “I agree,” reach out to them to see how you can help them to more fully meet your expectations. A lack of participation can be a sign of many things, including a learner misunderstanding requirements or a learner who has become more broadly disengaged for any number of reasons. With a little help, most learners can get back on track and be a full part of an online course community when they feel fully supported.

Taking a step back and considering the big picture

As already suggested, there could be many reasons why learners do not engage, or perhaps disengage, with class participation. Many factors pull on learners’ attention and ability to be successful in an online course. In Module 1, different dimensions of your learners were explored. Similarly, investigating gaps in learner engagement can be guided by a constellation of connected questions:

- Do learners have all the information (course content AND task instructions) they need to create a robust response?

- Are there elements of the participation requirements that could in fact be a barrier to participation?

- Are there different ways in which learners can express their participation (e.g., asynchronous text or video submissions after a live session) to contribute and demonstrate their knowledge and learning?

- Is there a lack of relevance in the participation ask? In other words, do learners understand why it would be beneficial to participate, or could they connect their learning of the discipline to their lived experience or apply their knowledge to real-life (or simulated) scenarios?

- Is it a time during the course where learners are likely to have competing deadlines for other courses and thus have deprioritized your course?

Finding out the answers to these questions may require you solicit information from learners individually (e.g., over email) or the whole class (e.g., posting a quick anonymous “check-in” survey in course announcements).

Showing empathy toward your learners in trying to determine what may be hindering their (that is, individual or whole class) engagement will often help learners feel acknowledged and heard and you are more likely to get honest feedback. Subsequently making small in-term adjustments in response to this feedback without jeopardizing your course learning outcomes can go a long way for the successful progression of your learning goals.

Assessing and revising your course will be further explored in a later section.

Using synchronous sessions

Live sessions are an increasingly popular aspect of many online courses, and they can be a highly effective tool for creating social presence in your course. Live sessions can give everyone in the course community a chance to see and hear one another in a more complete way, beyond merely text communications. But using live sessions carefully is key to keeping them effective for this purpose.

To maximize their utility for building social presence, think carefully about what you want to do in your sessions. We recommend that live sessions be used primarily for interactive discussions and activities rather than for lecturing, and that they be kept shorter than a typical classroom session.

Moving lecture materials to text or video format and keeping live sessions shorter helps reduce “zoom fatigue,” keeps student attention more effectively, and above all helps you leverage live sessions for what they are really best at: building more social presence. For instance, live sessions can be a great way to

- get to know learners and help them get to know each other,

- build rapport with your learners and create social presence within your course,

- answer learner questions and clear up confusion quickly,

- conduct certain types of discussions, and

- facilitate certain types of group work using breakout rooms.

Think carefully about your goals for a given live session and design it to maximize them. In addition, if you are going to deliver lecture materials and facilitate assignments asynchronously, you may be able to make your live sessions optional, offering even more flexibility for your learners while still allowing those who prefer to have some live time in their courses the chance to learn in a way that works well for them.

Examples of how synchronous sessions could work

Quality Essential

Example 3: Planning resources

Check out these resources from Boston College and University of Washington, which contain more tips on synchronous sessions and example plans for a synchronous course session.

Activity: Synchronous session plan

Learning outcomes

This activity directly aligns with Course Learning Outcome (CLO) 6: Structure and present your online content in ways that facilitate student learning and foster a sense of community and CLO 7: Employ effective facilitation strategies when delivering your online course.

Instructions

Create a specific plan for your next synchronous session (you can skip this activity if you are teaching only asynchronously).

- Begin by briefly summarizing the purpose of the live session you are planning. What are you hoping the session will add to your and your learners’ experience in the course?

- What learning outcomes will the session help you address?

- What are the essential components you want to include in your sessions (such as breakout rooms, discussions, active-learning elements, etc.)?

Next, create an outline of exactly what you would like to do in the session. Be as specific as possible, and designate how much time you expect to take on each portion of your session. You can save the resulting document for your planning purposes. You may also wish to share the document with your learners so that they can make the most of your session together.

Option 1: Download the Synchronous Session Plan Worksheet to create a Word version of this activity to complete offline.

Option 2: Use the below interactive to complete the activity. If you wish to save your in-line results, be sure to download your work by clicking the Export tab at the bottom of the left-hand navigation bar in the activity before moving on.

Please note, this activity is intended for your own reflection and learning. Your responses are private and are deleted when you refresh or navigate away from this page.